Making Doors with Mitered Corners

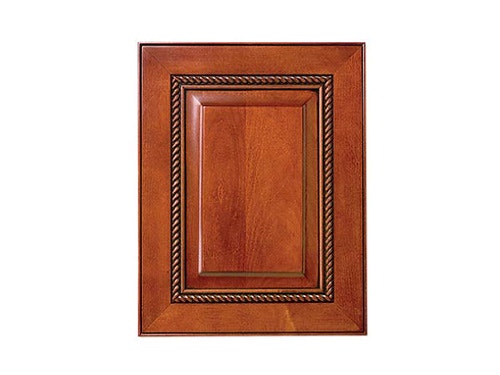

Does anybody have any instructions or ideas on how to make and glue up raised panel doors with mitered corners?

Here are a few thoughts:

If you are planning to make raised panel doors with mitered corners, a good place to start might be with asking yourself why. Most often, raised panel door frames are put together using a “cope and stick” joint. There are good reasons to consider doing things that way, instead of using miters. Most notably, a cope and stick joint is easier to make. With a router table, a "stile and rail" bit set and a little care, you can be virtually assured of a good joint appearance, and moreover, you can make the parts for several doors in a fairly short amount of time. A cope and stick joint also makes it possible to trim the door after it's assembled – you can take a little off of one edge, or trim the door slightly out of square to match an out-of-whack cabinet opening without any noticeable change in the appearance of the door or the joint.

Still, in certain situations a miter is the better choice. Door frames with elaborate profiles - or anything but a mostly flat face - won’t lend themselves to cope and stick joinery. And while there are a number of stile and rail router bit profiles available, the selection by no means endless. Since a mitered door frame does not require a perfectly-matching edge profile and cope cut, you’re free to experiment with a greater variety of decorative treatments. Or, you may just prefer the appearance of a mitered joint, and consider the extra care required worth the bother (an equally valid reason, as far as we’re concerned). Whatever the deciding factor, mitered joints have a few basic requirements.

As with any frame and panel construction, materials make a huge difference. For a door frame with mitered corners, it is especially important to choose flat, straight and properly dried stock. It is extraordinarily difficult to make a reasonable flat frame with four tight miters out of even slightly crooked lumber. Mitered joints are a little fussy when it comes to moisture content, as well. To avoid miters that pull apart on one end or the other, the stile and rail material should be dried to a moisture content that is as close as possible to a state of equilibrium with the environment where it will be used. If possible, consider using more dimensionally stable quarter-sawn or rift-sawn stock for the stiles and rails.

To get started, you'll still need to cut the panel groove on the inside edge of the stock, of course, and any decorative profiles. Once that’s accomplished and the panels are made, the next step is to plan and execute the joints. Mitered joints require reinforcement, especially when they’re used for something that’s likely to take a little banging around – like a cabinet door. There are a number of ways to reinforce a miter joint; a particularly fitting method for this application is to use a loose tenon. A loose tenon joint is easy to assemble, and will provide more than adequate strength for virtually any cabinet door. A loose tenon joint can be easy to make, as well - provided you’re willing to invest in one of a couple of specialized tools.

If you're feeling cashy, there simply isn't a slicker, easier way to cut a loose tenon mortise than the Festool Domino System. It's a considerable investment, but a worthy one if what you need or want is to make rock-solid joints in just about any type of construction in the same amount of time that it takes to pop in a couple of biscuits. For a little more work and lot less money, the BeadLock Jig will give you the same results. It’s another great, all-around alternative to traditional mortise and tenon joinery, and works out especially well for anyone who has trouble justifying the expense of the Domino or other more costly jigs.

Making the eight 45 degree cuts required to make the frame can be a sticking point. It sounds easy enough, but in practice, making a frame with tight fitting miter joints can prove frustrating – to say the least. If you've taken the advice above and are working with straight, edge-jointed stock that is relatively free of bow and wind (twists), following a few simple suggestions is almost a guarantee of success.

Getting the parts cut at the right length is an easy condition to meet. If you're using a chop saw to cut the joints, an auxiliary fence with a makeshift length stop will do the trick. Simply cut one end of each part, measure and clamp on a length stop at the appropriate place on the auxiliary fence, and cut both of the second miters for each pair of same-length parts using the stop as a reference. The resulting stiles and rails are guaranteed to come out in pairs that are exactly the same length. On a table saw the procedure is the same, except you'll use a miter gauge or a crosscutting jig to support auxiliary fence, the stop and the workpiece.

Miter cuts that aren't perpendicular to the face of the material can result in noticeable gaps in the joint, or in frames that won't lie flat. Fortunately, making cuts at a perfect right angle to the surface of a material – provided the material itself is flat - is simply a matter of accurately setting the angle of the blade. Rather than trusting the saw’s angle scale – a notoriously inaccurate method - place a square on the surface of the saw, hold it up against the blade plate, and adjust the angle of the blade until the two agree. Another approach is to use an electronic angle gauge. An electronic gauge, like the Wixey Digital Angle Gauge, will tell you in a matter of seconds that you have the blade set at a right angle – give or take a few hundredths of a degree.

Getting mitered joints to come out at a perfect 90 degrees is, for most people, the most challenging part of the procedure. But it doesn't have to be. The important thing to note is that two adjoining miters do not need to be cut at exactly 45 degrees – although that's a good thing to shoot for. In reality, it's more important that the angles add up to 90 degrees. The Rockler 45 Degree Miter Sled takes advantage of this fact, and makes cutting perfect 90 degree miter joints a simple, foolproof procedure. If you've had trouble in the past using the "two perfect 45s" method, we urge you to take a look at how this clever, affordable jig uses the concept of complementary angles to circumvent the problem.

Once you have all of the parts ready to go, it's a good idea to dry fit the entire assembly and make sure that all of the miters are satisfactory, the panel fits, the mortises are deep enough and in the right spot, etc. It's also a good time to run through a checklist of the supplies you'll need during the glue-up – clamps, glue, rags and so forth - and make sure they’re in reach. Remember that you'll need a clamping method that applies pressure both lengthwise and widthwise. If the parts fit together perfectly, a web clamp will do the job.

The great thing about learning to cut parts accurately is that when it comes time to glue up, the assembly will, in all likelihood, go together square and flat "automatically". It's still a good idea, however, to work on a surface that is itself as close to perfectly flat as possible. Once the clamps are tightened down, you can and check the door for flatness by sighting along its surface, and for squareness by measuring diagonally across opposing corners (the measurements should be equal). If you've worked carefully up to that point, the purpose in doing so will be to confirm that you’ve made your first perfect mitered raised panel door.

Keep the inspiration coming!

Subscribe to our newsletter for more woodworking tips and tricks