Butt Joint Variations

Bring two flat surfaces together with glue or other reinforcements, and you've created woodworking's simplest joint.

If you took shop class in school or have been making things from wood since childhood, a butt joint is likely the very first wood-to-wood connection you ever made. And it's one that we all continue to make throughout our woodworking careers. In fact, most projects are impossible to build without using butt joints in some capacity.

Butt joints are ideal when the speed of making and assembling a project is paramount, because the contact surfaces aren't modified to interconnect. There's no need to size the parts with added lengths, as with mortise-and-tenon joints, and no time-consuming machining of the joints themselves.

Many Variations

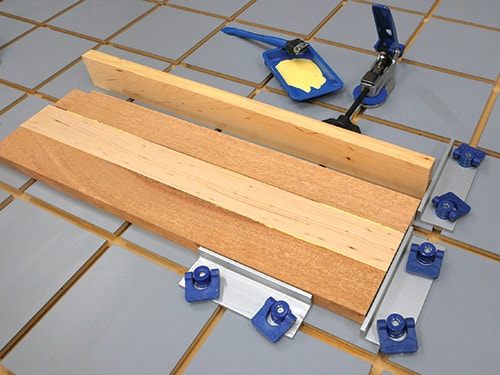

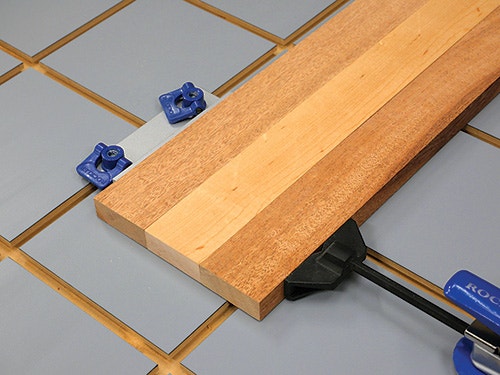

Butt joints encompass a variety of configurations when the square cut ends, edges or faces of two parts simply butt together to form a panel, frame, box, drawer or carcass.

Every time you glue two boards together to make a wider panel, you're creating a butt joint by combining parts edge-to-edge. Face-to-face butt joints are common when laminating layers of lumber together to fabricate thick leg blanks or butcher block assemblies from many strips of thinner wood.

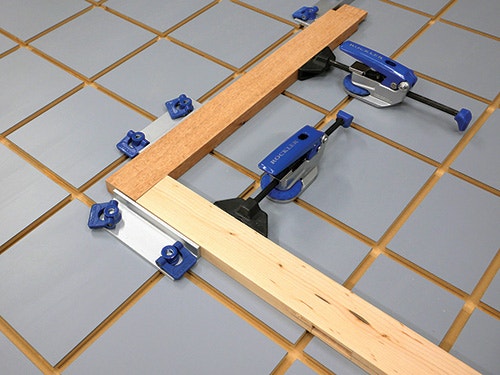

When you butt an end-to-edge to form an "L" shape, the combination creates face frames, simple picture frames and the like. Or consider the end- or edge-to-face connections required to create boxes, carcasses and the interface between a divider panel and a cabinet bottom.

In a pinch, you can even combine workpieces end-to-end to form longer components, but these end-grain butt joints are the weakest of them all.

Bring in Reinforcements!

Ordinary wood glue forms an incredibly strong bond between solid-wood parts joined edge-to-edge in panel construction. When properly made with fresh glue, the adhesive bond is actually stronger than the surrounding wood fi bers. Same goes for the long-grain contact surfaces of face-to-face laminations. But glue alone offers diminishing returns for other varieties of butt joints.

Here's when a butt joint's ability to resist common forces of tension, racking and sheer will depend upon a mechanical addition to the joint, such as nails or screws driven through the parts. Adding nails to a glued assembly, like a plywood or MDF box, bolsters the connection and helps to hold the workpieces together as the glue dries. However, it's best to reserve this kind of construction for light-duty uses; never use glued and nailed butt join ts to build a furniture frame or cabinet carcass intended for load-bearing or other heavy-duty purposes.

Screws and lag bolts further strengthen butt joints, principally due to the holding power of their threads and the stiffness of their shanks. Pocket screws are also highly effective, because both the screw shank and the washerhead are driven deeply inside the joint to maximize holding power and capitalize on the stiffness of the fastener.

Other simple but time-tested reinforcement options are glue blocks, which typically add some degree of longgrain connection to the joint, plus two more glued surfaces that secure them in a corner.

For even greater strength, butt joints can also be reinforced with wooden dowels, biscuits, Beadlock tenons, Festool Dominoes or splines. Most of these are easy to add to a basic butt joint, although they'll require some machine work and precision.

|

Strength: Moderate Difficulty: Easy Versatility: Extensive |

Keep the inspiration coming!

Subscribe to our newsletter for more woodworking tips and tricks