Avoid Tearout by Reading the Grain

If you can learn the tendency of how certain grain patterns react to being cut, you can avoid tearout. Looking for those predictable patterns is called "reading the grain."

In my opinion, the number one challenge in woodworking is avoiding tearout. Fortunately, it is fairly predictable if you know how to "read the grain." That refers to observing the grain pattern in a board and interpreting how its grain or tissue orientation will react when you are cutting it, especially in regard to planers and jointers (including hand planes). After teaching woodworking for many years, I find many woodworkers don’t understand the concept. While the practice of reading the grain is exceedingly helpful, even the most experienced person can be surprised by reversing grain.

When viewed from the end, a log's grain looks like a spider web (see the illustration at left). That grain as it presents in a board will tell you how it will react to cutting (see right illustrations). Those patterns (flat, rift and quartered) indicate where a board was harvested from a log. Riftsawn is the most difficult to predict which cutting direction will produce tearout.

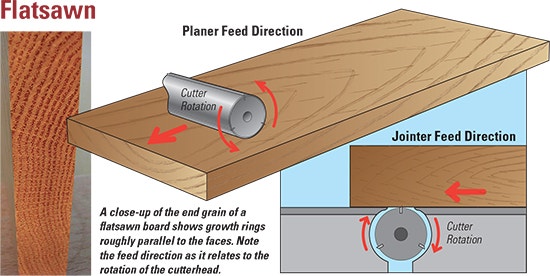

Flatsawn Lumber

Flatsawn lumber is the easiest grain to read, and also can tear out excessively if you try to "run the piece against the grain" through a planer or jointer. The growth rings in flatsawn stock are roughly parallel to the face, though they are curved. To joint or plane the faces, it's best to read the growth ring lines on the edge closest to the center of the tree. Woodworkers say that you always want to "cut uphill" on those lines. See the illustration at top right to clearly understand what that means. All machines cut against feed direction, meaning that you must be aware of the rotation of the cutterhead when using a jointer or planer. To mill the edges, read the direction of the rays on the face. Read them near the center of the cathedral patterns and remember that you should never read the cathedrals themselves.

Reading the rays on the face is easy on species like oak, sycamore and beech. It's harder to read on species like maple and cherry, but still possible. On open-grained but diffuse porous species like mahogany and walnut, read the coarse cell structure on the face. And on softwoods like pine and spruce, you can read the resin canals, if the species has any. With practice, you can accurately read the grain at least 95% of the time. Always test your choice by taking a very slight cut, and if tearout happens, flip the board the other direction and try again.

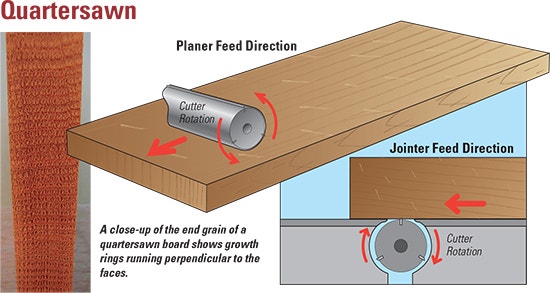

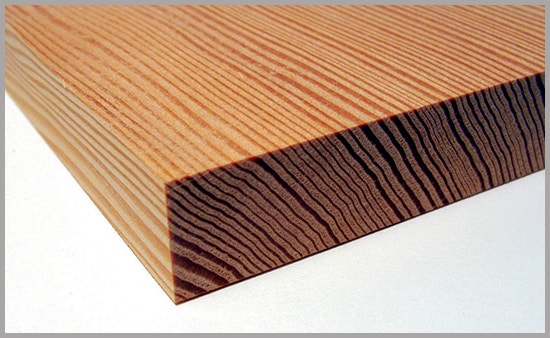

Quartersawn Lumber

Quartersawn stock is the opposite of flatsawn, in that the growth rings run perpen- dicular to the face. Again, think of a spider web, where the concentric rings are like growth rings and the radial lines are like the rays. So evaluate quartersawn stock in the opposite way to flatsawn stock. To cut the faces, look at the edges. The edge closest to the center will have tiny cathedral patterns (if properly quartersawn), but read the tiny rays running through them instead. To mill the edges, read the growth ring lines on the faces. Look to the bottom illustrations to understand the proper feed direction and cutter rotation.

Riftsawn Lumber

There is no clear-cut way to read riftsawn stock consistently because we do not see a proper cross-sectional view anywhere on the faces or edges. However, if a board is riftsawn on one side but gets closer to flatsawn on the other side (nearer the center of the tree), that is a key. In other words, by reading in the right places you can treat the board as flatsawn if it is close to flatsawn in one area. If, on the other hand, the riftsawn board starts to become almost quartersawn on the other side (the outside of the tree), then look to the growth rings on the face but really close to the edge which would have been the outside of the tree. And treat it as quartersawn. This is more difficult, so you have to stay on your toes.

On riftsawn boards where the growth rings on the end grain are 45 degrees to the faces and edges everywhere, it's more difficult. In that case, read both rays and growth rings on both faces and edges. Where rays and growth rings run the same direction, you’ll read the grain correctly for sure. Where they run in opposite directions, you're really just flipping a coin. Try light cutting in one direction to see how the wood behaves.

Worth the Effort

The fact is that we always have a 50/50 chance of making the right or wrong choice, but that does not reduce the value of reading the grain. Incorrect feed direction can and will cause tearout at the worst possible time. So just because some stock may be hard to read correctly doesn't mean we should abandon the practice altogether.

I haven't even talked in this short article about situations where the grain reverses direction once or twice or even more in a single board. In that situation, the best course is to cut according to what the largest amount of the grain indicates is the best feed direction. And where you observe that you have grain that twists profoundly or reverses within the length of the board, use extremely shallow cutting passes (and extremely sharp cutting edges).

Some high-figure grain patterns, such as bird's-eye and curly figure (e.g., maple) involve constantly reversing grain, and there is often no risk-free way to proceed. Quilted maple, crotch-grained mahogany and waterfall bubinga are some other grain patterns that will present this problem. Again, shallow cutting passes will be helpful, but shifting to scraping or sanding methods (including thickness sanders) will be most successful. Helical cutterheads will also help enormously. When using hand planes, use very high cutting angles.

Reading the grain will save you time and frustration. It is something every woodworker should learn to do. The good news is that you will get better at it as you work on it.

Keep the inspiration coming!

Subscribe to our newsletter for more woodworking tips and tricks